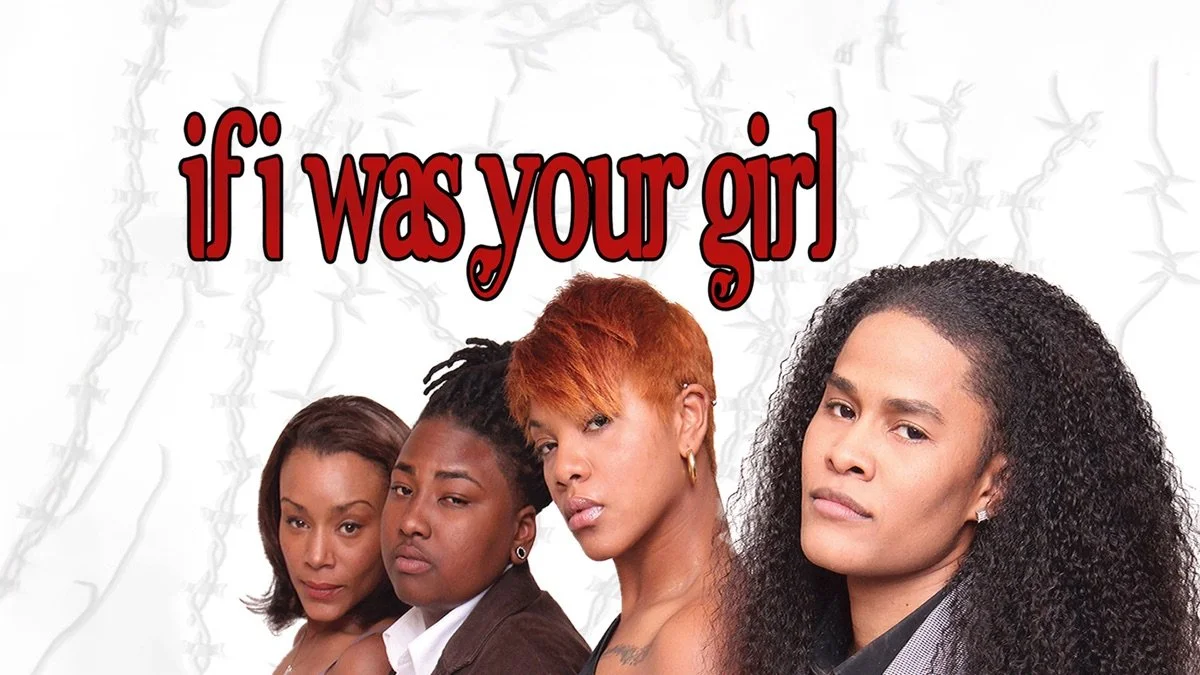

If I Was Your Girl

If I Was Your Girl (2012-2013)

Created, written, and directed by: Coquie Hughes

Charting the rocky relationships and ups and downs of four queer women (Toi, Stacia, Lynn, and Rhonda) in Chicago, If I Was Your Girl (2012–2013) is a thriller that goes back and forward in time to construct a narrative about serious issues in the queer of color community including incarceration, domestic violence, and suicide.

The decidedly scrappy drama bristles with kinetic energy as the four women fall in and out of love, threaten and save each other. Watching If I Was Your Girl reveals how safe and sanitized most queer representation is, particularly wrapped up in fantasies of uplift and respectability. The leads of If I Was Your Girl cross class, color, and gender, revealing how messy queer community really is.

In keeping with the goals of community-driven productions, creator Coquie Hughes (2013) explicitly cites her motivation—particularly domestic and state violence— to create works for the urban black lesbian community as inspired by her personal and social experiences. During our interview she states, “I wanted to use the film to let people to know that I was a lesbian…It kind of gave me that bravery I needed” (Hughes, pers. comm.). While Hughes's personal work is rooted in propagating representations of urban queer women of color, her roots are in community theater for city publics, and conversations around If I Was Your Girl started locally in Chicago at the Portage Theater in Portage Park, an ethnically diverse community with a growing black population. Hughes premiered the series in April 2012 to an almost sold-out audience of 1,100 people, not all of them queer, and premiered it again to a sold-out audience later that year. "The local people they liked it…The bootleg man really played a role in getting the word out," Hughes said in the interview. When she sold the version online after the premiere, she grossed $12,000.

If I Was Your Girl was massively popular online, challenging the idea that traditional production value is critical to widespread reception and showing how writing and cultural sincerity are key to stories resonating with community both online and in person.

Hughes’s impressions of local reception mirror online dynamics, revealing how the performances she captured—she cites the attractiveness of actors as key—produced complex sexual response from queer and nonqueer viewers alike: "I get more so straight people who relate to my projects…A lot of straight people come to my premieres. They say 'I'm not gay but…' so and so is gorgeous…People get all kinds of emotions" (Hughes, pers. comm.). Hughes cites the complex politics of recognition in black production and reception. The black community's invisibility creates excitement, drawing diverse crowds for queer content; yet media's hypervisibility and the independent-mindedness of creators intensifies conversations around representations of blackness. Series by producers like Hughes clarify and challenge the boundaries of black community. Black production and performance online is an innovation in television development with social but also economic value. As Hughes stated in the interview: "I didn't plan on making films for the urban lesbian community. I'm just taking advantage. Ain't nobody making content for this community because they don't care…They will pay to see themselves." For Hughes, modest financial gain is an unpredictable side effect of providing places online and off-line for a public eager to engage with the queerness of black social dynamics.

If I Was Your Girl is different from Between Women, No Shade, and many of the other Black queer indie series popular at the time in content and comments because of its sexually explicit portrayal of black queer women, which has resulted in an inordinate number of comments from nonqueer, religious, and/or homophobic viewers. This pushback seems to be indicative of the fact that If I Was Your Girl veers away from the safe and sanitized portrayals of lesbian couples that viewers are used to seeing in other Web series and network TV in order to visibly represent the fullness of lesbian sexuality. Embracing these representations, there are also many viewers of the series who truly enjoy the series because of the overt representation of lesbian sexuality. In the comments section, there are multiple examples of the parasocial relationships that fans developed with the queer characters and couples as a result of this attraction (note 1). As one commenter states, "You never see lesbian shows on the tv so thats y theres youtube:)…smh [shaking my head] u people are mad because [you] disapprove of homosexuals lol [laugh out loud] o wel." Hypersexualized queer individuals do not operate within respectability politics, but viewers see Web series as a unique space where producers should push the boundaries of what is acceptable in the mainstream. If viewers do not approve of these representations, then the content is probably not for them.

***

Sections of this article were adapted from Faithe Day & Aymar Jean Christian, “Locating Black Queer TV: fans, producers, and networked publics on YouTube,” Transformative Works & Cultures, https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/867